Nigerian Modernism

A Review of the landmark exhibition at the Tate Modern

Modernism is typically framed as a Euro-American story. Parisian artists break with the conventions of academic art, ditching naturalism for experimentation. A relay of movements—Impressionism, Fauvism, Cubism—emerge from this impulse, each successive movement defining itself against what came before.

Modernism is also, quietly, a colonial story. The self-confidence and experimental licence we associate with European modernity was supported by empire. Objects taken in punitive raids from African precolonial polities and anthropological missions—Nok terracottas, Ife heads, Benin bronzes—circulated in Paris and London as "primitive art," stripped of their political and spiritual meanings. Picasso, Modigliani, Giacometti and others learned from those objects what classical models could not teach; the artistic senibilities of their makers was meanwhile dismissed as instinctive and childlike. The myth of modernism and the machinery of empire grew together.

For colonised peoples, including those who would later be folded into the Nigerian nation, the consequences were double. Twentieth-century artists had limited access to their own historic objects because so many had been removed to European museums. Additionally, colonial schooling was designed to produce clerks, not artists. Where art was taught, it sharpened handwriting and draughtsmanship for bookkeeping and technical drawing. To make "art" for exhibition was to work inside a system that barely recognised you as an artist at all.

This is the ground on which Nigerian Modernism: Art and Independence at Tate Modern stands. The show asks what it meant to make modern art when your past had been exported, your visual traditions misread as primitive, and your schools trained you to copy better, not think differently. It also tests the word modernism itself: can a term forged in the metropole bear the weight of many, conflicting Nigerian art histories? The exhibition is presented with major Nigerian backing from Access Holdings and Coronation Group—alongside the A. G. Leventis, Ford and Andy Warhol foundations. This support led by Nigerian institutions reflects a duty of stewardship, and a demand that Nigerian art sits at the centre of the modern story, not at its edge.

Curated by Osei Bonsu with Bilal Akkouche, the show spans 250-plus works from the 1920s to the 1990s. Rather than a single arc of progress, each room answers a version of the same question: what does it mean to make modern art in Nigeria? Are there Nigerian modernisms—plural—or one global modernity into which Nigeria is folded by history?

Fig.1. Ben Enwonwu, Black Culture, 1986. (detail). exhibition catalogue paperback cover.

Opening Provocations

We begin with Aina Onabolu [see Fig.2.] and Akinola Lasekan, the first generation formally trained in European techniques. After an education in London and Paris, Onabolu returned to Nigeria and established himself as a painter to the elite. He campaigned for a Lagos curriculum which included the most foundational European artistic developments, such as perspective, anatomy and oil paint. Sisi Nurse (1922) and Portrait of an African Man (1955) deploy the grammar of European portraiture to picture Nigerian status on Nigerian terms. Lasekan extends that training into public argument: his West African Pilot cartoons skewer colonial officials, making modern art a tool of critique as much as culture.

Fig.2. Aina Onabolu, Portrait of an African Man, 1955. oil on canvas.

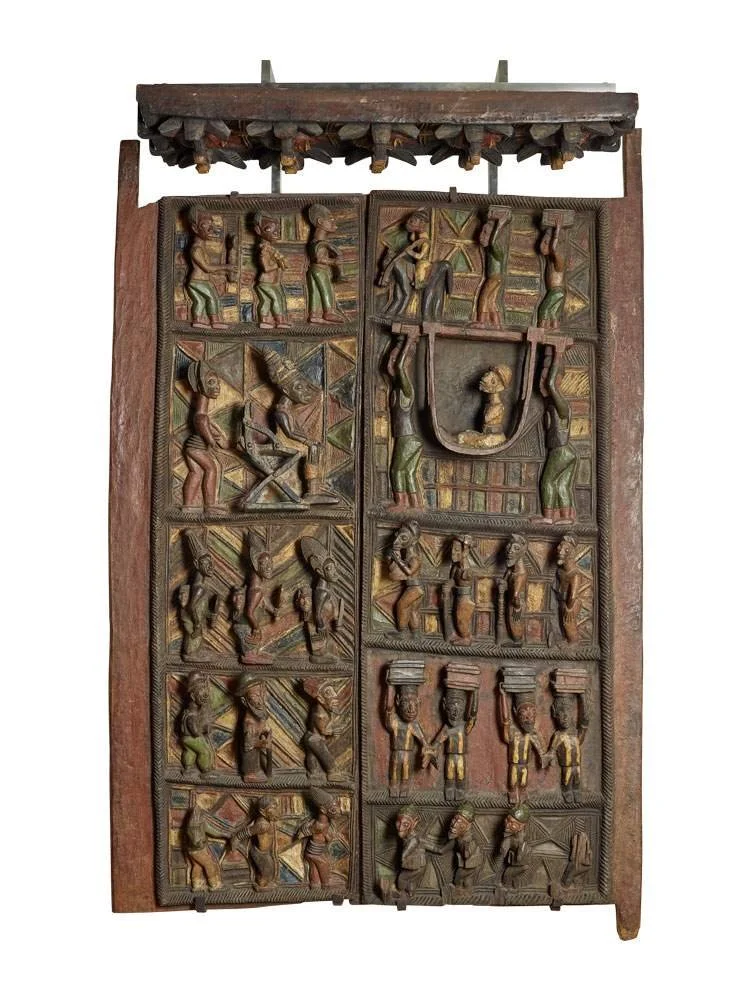

Fig.3. Olowe of Ise, Pair of wooden door panels and lintel, c.1910–1914. wood.

Towards the end of the display in the first gallery is a quiet provocation. A palace door by Olowe of Ise [Fig.3.], shown at the 1924 British Empire Exhibition, depicts royal audience interrupted by a British officer carried by porters, with frieze-like depictions of servants, subjects and shackled prisoners below. The style is wholly Yoruba; what is "modern" is the period of its execution and subject matter—a precolonial medium picturing a reordered world. Nearby, Jonathan Adagogo Green's studio photographs of Niger Delta chiefs arrive within decades of photography's European invention. The room argues that modernity is a shared, uneven present, not delayed delivery from Paris.

Still, if you are going to claim the door as "modern," why stop there? Where are the bronzes produced in the late 19th century to triangulate the point? And if modernism is the chosen term, why not set this opening in dialogue with the European modernism that fed on African form? Indeed, Picasso was Onabolu's contemporary. This omission is no doubt intentional—the curators admirably sought to define Nigerian modernism in relation to itself. However, especially for those aware of the colonial legacy of modernism, one feels the absence of a confrontation with themes of cultural appropriation and the charge of primitivism placed on the artwork produced by twentieth-century African artists.

Ben Enwonwu: Nation-Builder

Fig.4. Ben Enwonwu, Anyanwu, 1954-1955. bronze.

The next room tightens its focus on Ben Enwonwu. Born in Onitsha to a shrine sculptor, trained at the Slade, moving between Lagos and London, Enwonwu sits where tradition, nationhood and international visibility intersect. Here the appropriation question features briefly. The descriptive panel for an iconic Enwonwu sculpture Anyanwu (The Rising Sun) (1979–81) [Fig.4.] explains that critics routinely compared his attenuated figures to the work of Swiss sculptor Alberto Giacometti. Enwonwu's retort makes clear the importance of resisting this narrative to African artists of his generation: that Giacometti had already been influenced by his "ancestors".

Fig.5. Ben Enwonwu, The Dancer (Agbogho Mmuo - Maiden Spirit), 1962. oil on canvas.

This second gallery is a feast for the eyes. Anyanwu depicts an Igbo earth goddess stretched skyward, created to commemorate Nigerian independence. On canvas, works like Agbogho Mmuo (Maiden Spirit) [Fig.5.] turn the blur and tempo of masquerade performance into paint; Enwonwu captures the torque of his dancer's torso, the glare of the masks and the rhythm of the drums. The chief criticism here is the wealth of rich objects displayed. One leaves awed by the scale of Enwonwu's practice, but less clear about how his forms mirror the nation-building project in post-independence Nigeria. That notwithstanding, I imagine that the curatorial urge to display such a breadth of work would have been irresistible.

Fig.6. Ben Enwonwu, Seven wooden sculptures commissioned by the Daily Mirror in 1960, 1961. wood. (Installation view)

Ladi Kwali and the Craft Question

Ladi Kwali's room is a quiet triumph. Raised in a Gwari community, Kwali learned coil-built pottery and open-kiln firing before joining Michael Cardew at the Abuja Pottery Training Centre to work with the wheel and high-fire glazes. Water jars and casseroles incised with lizards, fish and abstract bands bind function, symbolism and technological experimentation. Placing Kwali structurally alongside Enwonwu's gallery collapses the art/craft hierarchy and insists that modernism exists within indigenous craft traditions.

Fig.7. Ladi Kwali, Installation view of various ceramic vessels.

But why carve out the space and stop short of context? One or two juxtapositions—perhaps Kwali beside Bruce Onobrakpeya's relief prints, or Uche Okeke's linear compositions—would have made formal continuities between these modernists explicit. The gesture is unmistakably there, but in the commendable decision to give Kwali the focus of her own gallery, the sense of her connection to other Nigerian artists is hushed.

Zaria: Natural Synthesis as Method

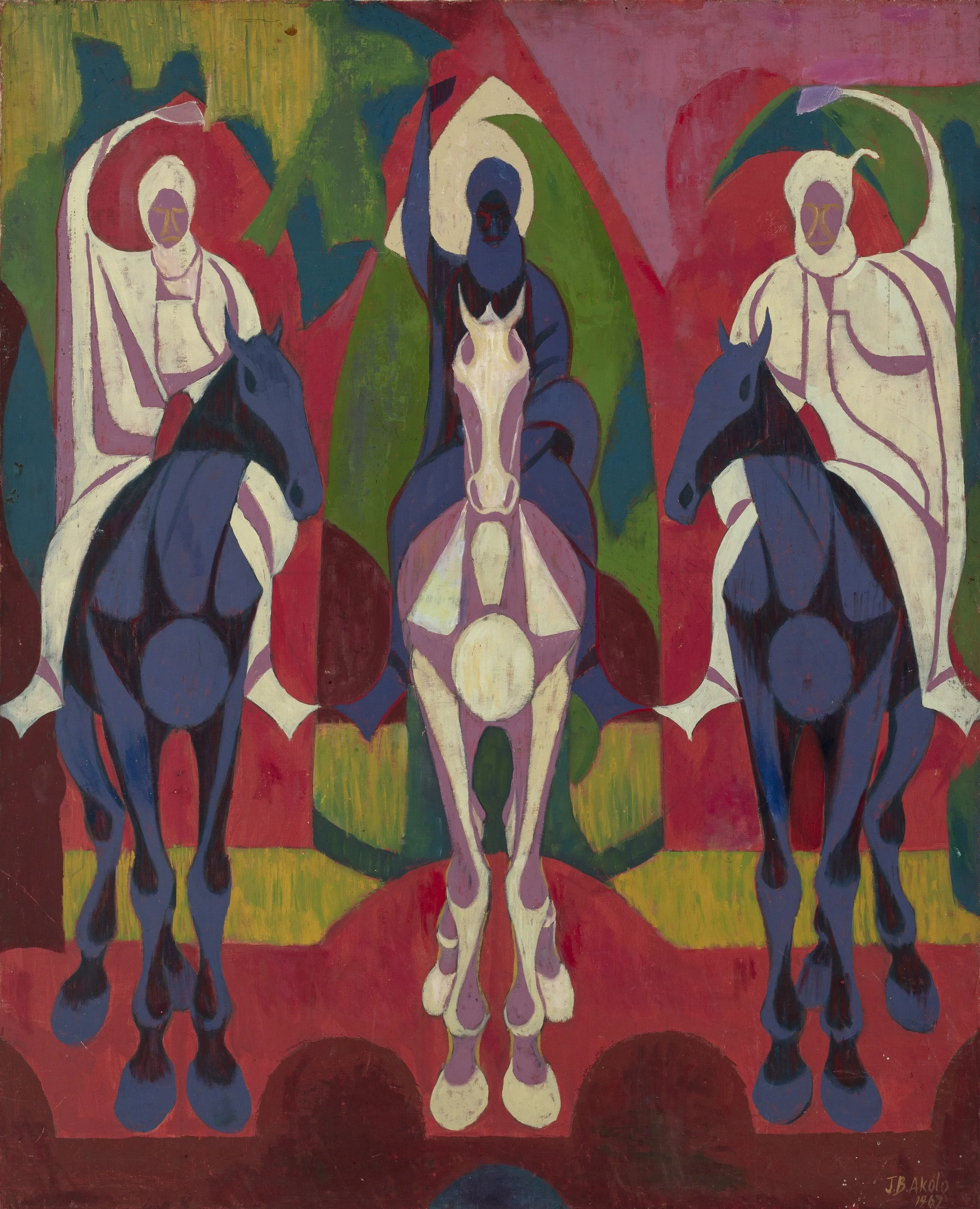

Fig.8. Jimo Akolo, Fulani Horsemen, 1962. oil on board. (detail)

The next gallery display, Zaria: New Art, New Nation, illustrates most clearly the comprehensive formal experimentation of Nigeria's academically trained artists. In the late 1950s the Zaria Art Society, formed by Uche Okeke, Yusuf Grillo, Jimo Akolo, Demas Nwoko and others, crafted a new movement for postcolonial modern art named Natural Synthesis. It is marked by a focus on indigenous visual cultures like Igbo uli script used in body art and wall murals, as well as other bodies of precolonial visual culture, and fuses these traditions with what is useful from European training like perspective and anatomy, discarding the rest. Calling it "natural" was a tactical understatement, shielding a rigorous method from the charge of primitivism and sketching a blueprint for image-making in a country that had never previously existed as one nation.

On the walls Natural Synthesis is made legible as practice. Okeke's uli drawings depict folktale beasts with a unique lyrical abstraction. Grillo's ultramarines read as stained glass and indigo textile at once. Akolo's Fulani Horsemen [Fig.8.] compresses motion into a patterned frieze at the picture plane. Early El Anatsui works hint at the stylistic offshoots of the Natural Synthesis philosophy. This gallery truly imparts the viewer with the sense that the Zaria Art Society comprised a school of art, a modernist movement with truly indigenous origins and aims.

Nsukka: The Language of Catastrophe

Fig.9. Obiora Udechukwu, Our Journey, 1993. ink and acrylic on canvas. (detail)

Similarly, the display Signs of Life: The Nsukka School beautifully demonstrates the evolution of Natural Synthesis after the moment of independence. Between 1967 and 1970 Nigeria is torn by civil war; over a million people, mostly Igbo, die from violence and starvation. After the war, Okeke leads Fine Art at the University of Nigeria, Nsukka, relocating Natural Synthesis from its national origins to reflect the concerns of his local Igbo ethnic group. The Nsukka School, comprised of artists like Obiora Udechukwu [see Fig.9.], Chike Aniakor, Ada Udechukwu and others, uses Igbo scripts like uli and nsibidi to forge a quiet, exacting language for confronting grief and the instability of daily life. Thin, searching lines gather to form queues and markets; patterns sit on bodies like scars. Under Christopher Okigbo's poem "Come Thunder," the drawings read as parallel texts, not illustrations. If Zaria proposed a nation-wide method, Nsukka distils it into an Igbo modernism that is unconcerned with its ties to modernity or nation-building. It asks, instead, what kind of line can hold catastrophe.

What the Exhibition Leaves Unsaid

Fig.10. Ben Enwonwu, Installation view.

One does not leave Nigerian Modernism with a binding curatorial thesis. Perhaps intentionally, the exhibition prioritises giving you the artworks over telling you how to think. For a general public, that generosity is welcome; for specialists, it is a missed opportunity to take a stance. The exhibition has little by way of an overarching theme, no clear rules of thumb to describe the evolution of art practice through the decades, and no unifying theory of Nigerian Modernism you can carry out of the building. The sense is of a foundation-laying gesture: to start afresh, make Nigerian modernism visible and prompt prominent institutions to collect, rather than to impart an incisive argument.

That focus matters. Other shows like Paris Noir at the Pompidou, A Black Atlantic at the Art Institute of Chicago and Tropical Modernism at the V&A have sketched parts of this terrain, but a national focus increases the pressure to develop deep and specific collections. As a public proposition, Nigerian Modernism is essential and important. It will nudge acquisitions. It gives younger Nigerian and diasporic artists a visceral connection with the creative production of their ancestors.

Where it falls short is where its title over-promises: modernism. The exhibition admirably treats Nigerian art in relation to itself, but the term inevitably summons primitivism and appropriation, the very pressures Nigerian artists had to counter as they built a national tradition capable of reclaiming motifs taken from them. Here lies the deeper contradiction the exhibition does not fully address: these artists were not outside European modernism—they were constituents of it. They went to the same schools, consumed the same artistic influences, and contributed ideas to the development of modernist thought. They were also doubly conscious of the other side of ruthless industrial progress: the extraction and exploitation of the Global South that underwrote European wealth.

When the call came to transform a colony optimised for economic extraction into an independent nation, these artists answered by building a national artistic tradition. This is the story of how artists navigated creating a "decolonial" art form to frame national cultural identity whilst being beneficiaries and intellectual constituents of that colonial system. If you remove the West from the story, you risk telling an incomplete one—because those artists did not define themselves purely on their own terms, but in relation to the world. They created artistic traditions that had to be inwardly looking, yes, but they were influenced by the West even as they sought to avoid replicating its cultural systems. Uli, Natural Synthesis, Zaria—which really is the only movement that developed a rigorous philosophy—represents in one sense a contemporary Nigerian art form resistant to claims of being derivative of either African or European art. But it also reflects an equal consideration: making a contemporary art form appealing to Nigerians themselves, not just commercially but as something they would accept as part of their heritage.

The curators understand this complexity intimately. If you are fortunate enough to receive a tour from Bonsu or Akkouche, you will note that the artworks themselves call forth these narratives. I just wish there had been a way of bringing out this history more plainly—some method other than wall text, or specialist knowledge, or guided tours.

The Verdict

The show embraces "multiple modernisms" without equipping visitors to ask the harder question that phrase points to: why should this extraordinarily diverse web of practices—rooted in different languages, religions, regions and diasporas—be gathered under a single label that originated elsewhere? Yet, the fact remains that once you have seen Olowe's door, Enwonwu's sculptures, Kwali's jars, Okeke's beasts, Grillo's blues, Oshogbo's spirits and Egonu's vorticist cityscapes gathered with this confidence, it becomes impossible—intellectually and institutionally—to treat Nigerian art history as peripheral, or to keep telling modernism as a Western story with African cameos. The terms may be contested, but the result is clear: modernism has expanded beyond its European bounds. The success of this exhibition is in its dedication to writing Nigeria into the core of the story of modern art.