The Histories/ The RYTHM MASTR Chronicles

A Review of Kerry James Marshall’s Double Act in London

A curious contradiction lies at the heart of Black cultural production in the West. Black culture is indelibly entangled with the European tradition, yet it emerges from a legacy of marginalisation into a bastardised category ('Negro' art) which was from the outset construed as primitive. The implications of this paradox are obvious at the extremes: should the Black contemporary artist reject the West outright, they must invent speculative artistic traditions to avoid conflation with that backwards Negro art. If instead they adopt the language of the Western tradition uncritically, their production becomes vulnerable to alienating their own inheritance in the intellectual tradition of the West. With a duo of exhibitions in London—"The Histories" at the Royal Academy and "Rythm Mastr: The Chronicles" at the Tabernacle—Marshall demonstrates an unrelenting commitment to interrogate this problem fearlessly.

Curated by Mark Godfrey, "The Histories" is the largest presentation of Marshall's work in Europe to date: 70+ works spanning five decades. Marshall, born in Alabama in 1955 and now based in Chicago, is given the breadth he merits, and Godfrey uses it to stage a simple but radical through-line: Blackness belongs in art history first as a physical, then figurative fact, and only then as a conceptual proposition.

Fig.4. A Portrait of the artist as a shadow of his former self (1980). egg tempera on paper

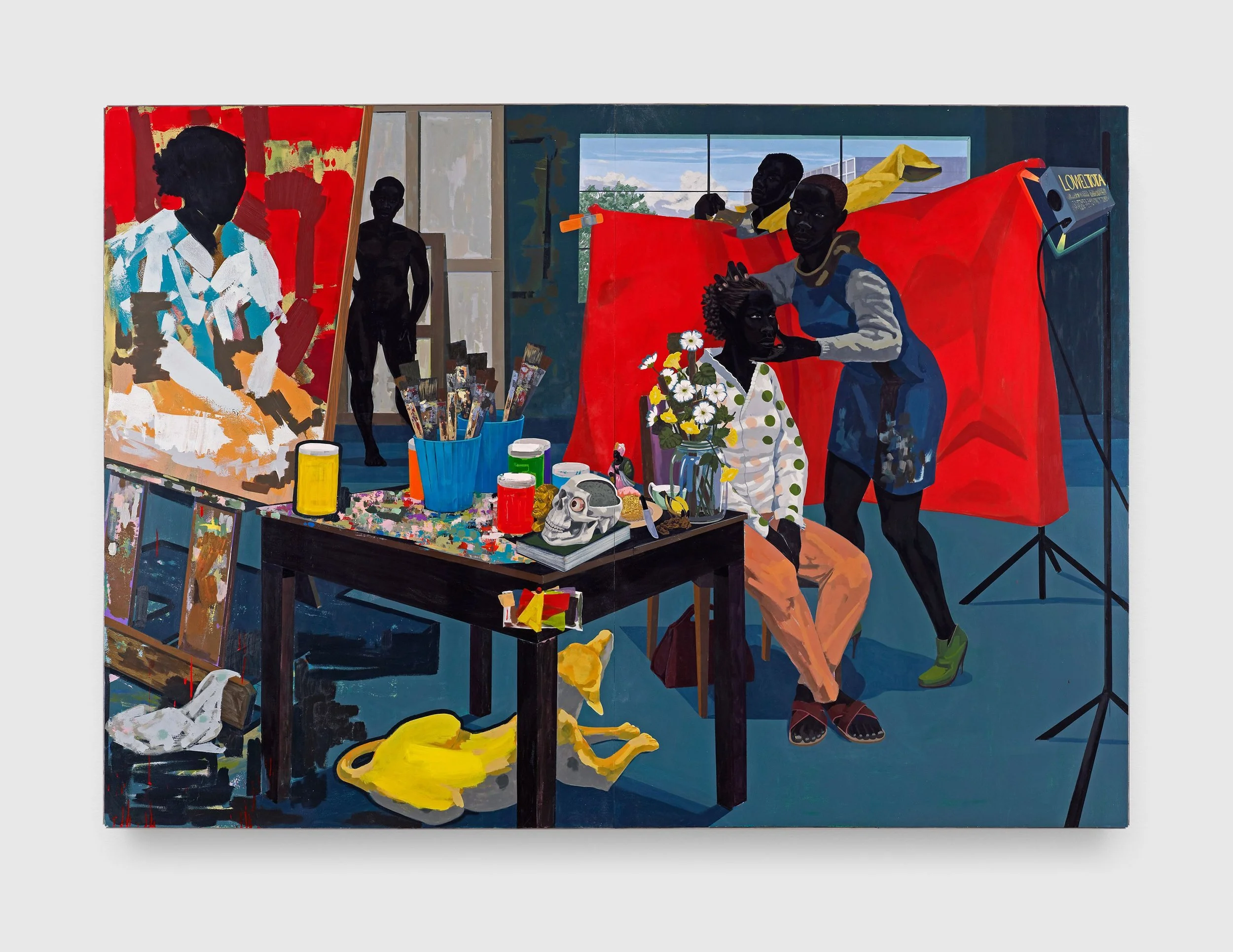

That insistence is explicit from the outset. In the first two of eleven rooms, Marshall depicts Black artists, Black models posing for Black artists; Black schoolchildren occupy the studio, the academy, and the museum (The Academy (2012) [Fig.1.], Untitled (Studio) (2014) [Fig.2.], Untitled (Underpainting) (2018) [Fig.3.]). Godfrey begins the exhibition with a focus on Marshall's reflections on the representation of Blackness in art. Take, for instance, A Portrait of the Artist as a Shadow of His Former Self (1980) [Fig.4.], which shows a Black figure against a dark ground, its facial features nearly indiscernible. Marshall seemingly flattens the figure into a single plane; the haunting caricature compels the viewer to examine its surface, revealing layers of pigment applied with a scratch-like. He uses egg tempera, a medium associated with pre-Renaissance painting whose quick-drying layers add a hazy delineation between forms. In these works, Marshall builds figures from ivory black, mars black, and carbon black, layering and juxtaposing them so that "black" becomes fully chromatic—not an absence of colour but luminous and vibrant. In this sense, Marshall paints Blackness into the canon as pigment, so that its presence in art precedes conceptual discourse.

Fig.1. The Academy (2012). acrylic on PVC panel

Fig.2. Untitled (Studio) (2014). acrylic on PVC panels

Fig.3. Untitled (Underpainting) (2018). acrylic and collage on PVC panel in artist’s frame

Yes, Marshall looks to assert the presence of Blackness in art history, but he is not content to make a single gesture alone. The exhibition note for The Academy quotes Marshall with a succinct explanation of this gesture: "If you say Black, you must see Black." His choice to depict figures using Black pigment demonstrates his intention to physically paint Blackness into art history. He first insists that painting itself must accommodate the full spectrum of Black. Only after making this point plainly does Marshall's practice open up to allegory, history, and engagement with the canon. Hereafter, the exhibition's focus reverses from the place of Blackness in art toward an examination of art's capacity to represent and reflect Blackness.

Fig.5. School of Beauty, School of Culture (2012). acrylic and glitter on unstretched canvas

The exhibition is dominated by Marshall's large-scale compositions, where his grasp of the Western tradition becomes inescapable. School of Beauty, School of Culture (2012) [Fig.5.] is a tour de force: a salon staged like a Renaissance tableau. Women sit in chairs and dance between stations; conversation and commerce hum. Around them, the salon's iconography: Dark & Lovely posters (an ode to the Black is Beautiful movement which uplifted Black beauty standards), the pan-African flag motif, a signed Lauryn Hill album cover, a 2008 Chris Ofili exhibition Tate poster, and a portrait of the artist's wife—all rendered in the painting with the painterly language of European noble history painting and portraiture. The composition brings to mind the quiet stately grandeur of Velázquez's Las Meninas (1656) [Fig.6.], the order of Leonardo's Last Supper (c.1495-1498) [Fig.7.], or the symbolism of Holbein's The Ambassadors (1533) [Fig.8.], the latter a work directly cited as a reference for School of Beauty. The memento mori (a symbolic motif signifying mortality) which famously takes the form of a skull in Holbein's work is here recast as a skewed, glittering depiction of Disney's Sleeping Beauty running diagonally across the picture plane. This is where Marshall introduces critique into his work: where the skull in Holbein's work represents a reminder of the inevitability of death, does Sleeping Beauty under Marshall's hand point to the looming subversion of Black culture in the very spaces in which it thrives?

Fig.6. Diego Velázquez, Las Meninas (1656). oil on canvas

Fig.7. Leonardo da Vinci, The Last Supper (c.1495-1498). mural painting

Fig.8. Hans Holbein the Younger, The Ambassadors (1533). oil on wood

Fig.9. Ernie Barnes, The Sugar Shack (1976). acrylic on canvas

School of Beauty undoubtedly celebrates Black culture, invoking the sense of joy and vibrance of canonical works like Ernie Barnes' The Sugar Shack (1976) [Fig.9.]. Yet, Marshall insists on emphasising to the viewer that The School of Beauty is, to some unavoidable extent, a space wherein aspiring hairdressers learn to apply products designed to straighten Black hair into conformity, to style it into digestibility. Ironically, the Dark and Lovely posters Marshall repeatedly depicts reference the haircare brand of the same name, once a Black owned company, now sold to a European conglomerate. With challenging and arresting pictures like School of Beauty, Marshall moves beyond the assertion of Blackness in art history, instead turning history painting outward to face Black life.

Fig.10. Past Times (1997). acrylic and collage on canvas

Similarly, Past Times (1997) [Fig.10.] transposes the modernist masterworks of artists like Manet and Seurat into a depiction of a family picnic in a Chicago park. On the surface, they radiate leisure. In context, they vibrate with contradiction. Families lounge with housing projects at their backs; radios drift lyrics from Snoop Dogg—songs where the pursuit of money, desire, and status becomes a mantra for ambitious urban youth. The work takes on a deeper significance when we consider its provenance. The work was acquired by Sean "Diddy" Combs for $21m (with premium) at Sotheby's in 2018, still a record sum for an artwork by a living Black artist. Viewed in this context, Past Times shifts from a reflection of the aspiration and leisure of Black family life to the encapsulation of the contradictions of the American dream, the ruthless pursuit of which has crystallised connotations of danger and criminality for the Black individual in white society. In this sense, Marshall captures a contemporaneous double consciousness with a precision the nineteenth-century moderns sought but rarely reached. The conceptual devices of Western academic and modern art, operationalised from Marshall's marginalised perspective, illuminate human life with an unprecedented level of depth.

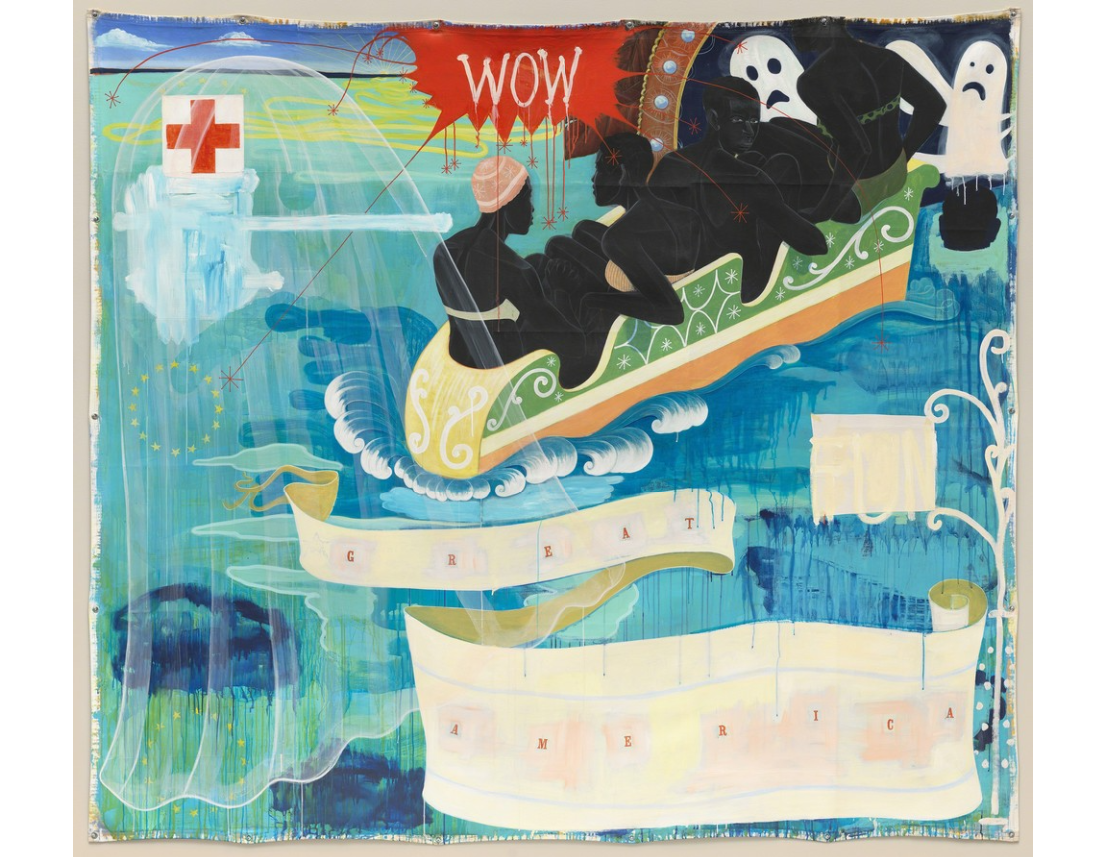

Fig.11. Great America (1994). acrylic and collage on canvas

Fig.12. Terra Incognita (1992). acrylic, ink and paper collage laid on canvas with metal grommets

Fig.13. Exhibition view: Wake (2003–ongoing). model sailboat, pedestal, medallions, photographs, black light photographs and gold chains. Before Gulf Stream (2003). acrylic and glitter on canvas

Marshall pushes further into the examination of Black history with a focus on Africa. Works like Great America (1994) [Fig.11.] and Terra Incognita (1991) [Fig.12.] reference the Middle Passage obliquely, fragmenting the story of the countless Black souls lost overboard slave ships in the Atlantic through semiotic references to popular visual culture like amusement parks and Yoruba iconography. Unlike European modernists who plundered African art for stylistic novelty, Marshall invests in its symbolic and spiritual power. The Kongo nkisi nkondi—spiritual doll figures whose power is activated and heightened by the insertion of nails into their surface—becomes a central metaphor. In Wake (2003–ongoing) [Fig.13.], the nails are referenced by the inclusion of medallions commemorating prominent Black figures, each new addition strengthening the work's potency. This is not appropriation of African culture but synthesis: African ritual practice carried into Western painterly form, a gesture that transforms both.

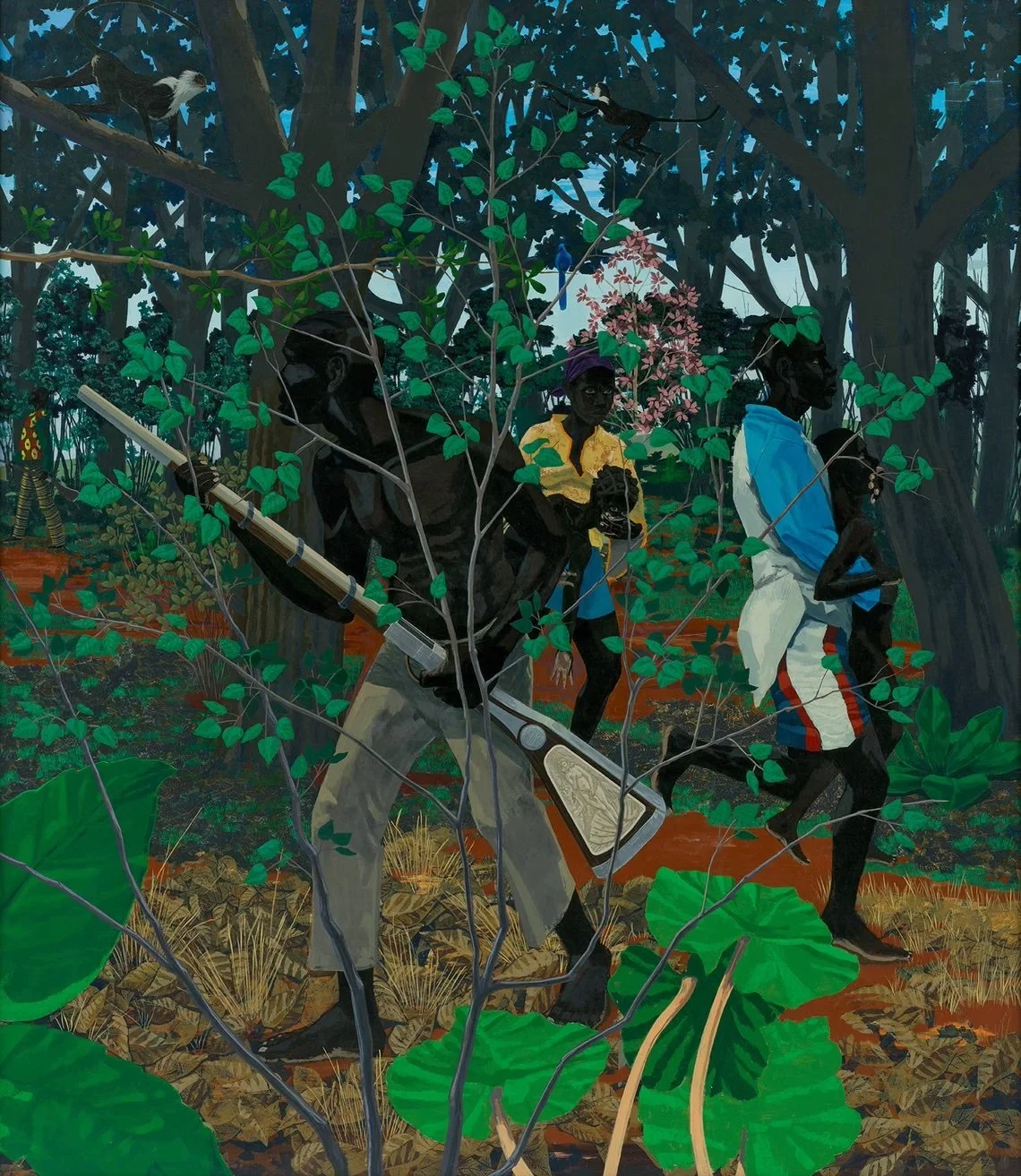

Fig.14. Abduction of Olaudah and His sister (2023). acrylic on PVC panel in artist’s frame

Fig.15. Haul (2024). acrylic on PVC panel 3 in artist’s frame

The most recent works refuse simplification altogether. Abduction of Olaudah and His Sister (2023) [Fig.14.] and Haul (2024) [Fig.15.] confront African complicity in the slave trade, while the White Queens of Africa series reimagines the colonial entanglements of European women who married African leaders. Marshall embraces the nuances and controversies of the historical record; his vivid and lush pictures of Africans confront the greed of Africans involved in the slave trade. Yet, his attention to the land and seascapes suggest an almost nostalgic affection for the African homeland. Marshall maintains his imperative to centre Blackness even as he heightens the contradictions its history carries.

"The Histories" is unequivocally of the highest calibre of monographic survey exhibitions. If there was any criticism one would offer, it might be that in rising to the grandeur of the Royal Academy, the exhibition may reinforce the hierarchies of the European tradition: that of 'High' art and history painting, of blockbuster exhibitions in the world museums of colonial capitals. Marshall shrewdly escapes this criticism with the second act of his triumphant showing in London.

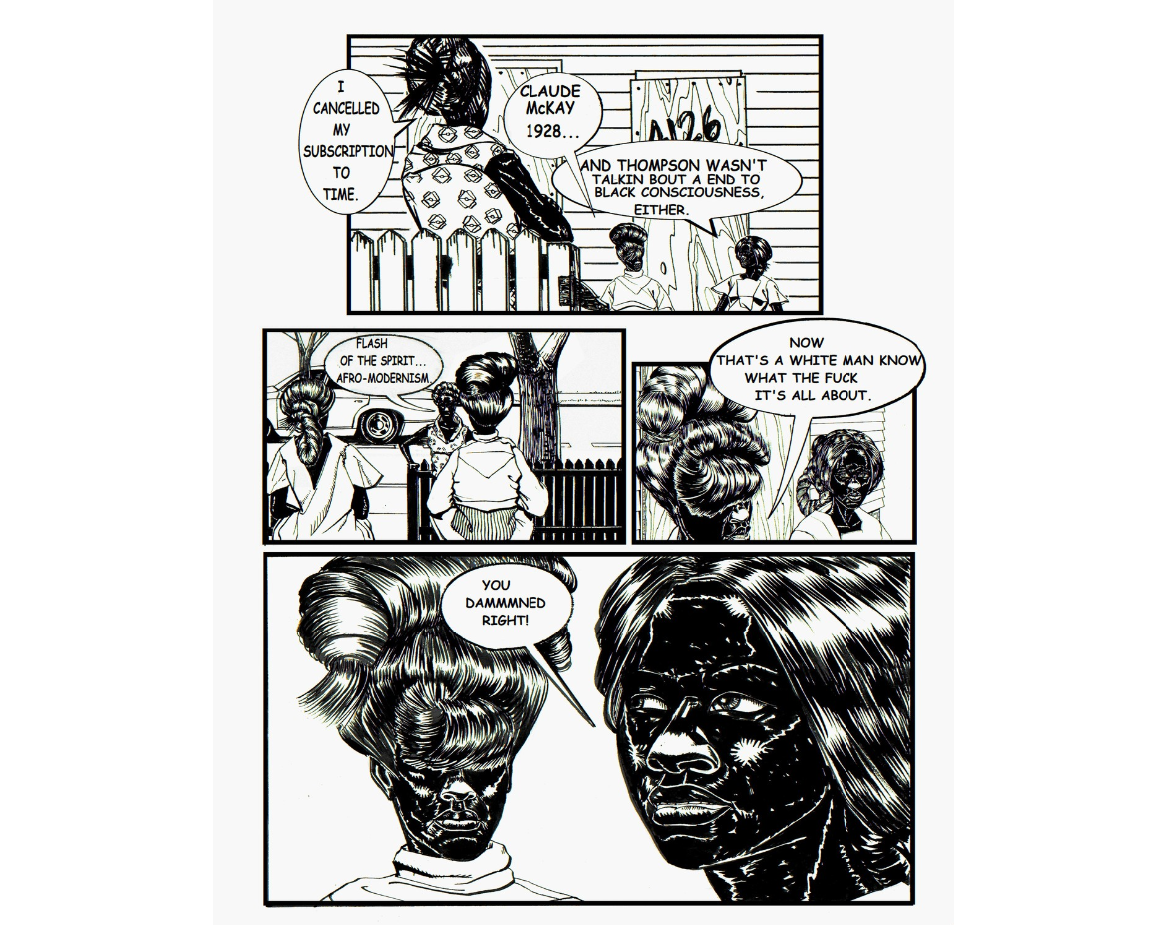

Fig. 16. Rythm Mastr (1999–present)

“Rythm Mastr: The Chronicles” is staged at the Tabernacle in Notting Hill, a community space tied to the origins of Carnival and a venue central to the Black community in London. Curated by Godfrey and Nikita Sena Quarshie, the show gathers a selection of printed works produced over 25 years as part of Marshall's Rythm Mastr project, an imaginary superhero saga set on Chicago's South Side in which African artefacts awaken through drumming to fight crime. The project in this popular cultural medium began in response to his desire to see more Black heroes in his favourite comic books. Marshall takes this popular medium and loads it with his most direct intellectual arguments. He is blisteringly clear in one passage of conversation between two women in his comic: "If you say post-modern… you might as well say post-Black. What I look like talkin' 'bout some 'post-Black' while whiteness remains intact, dominant and privileged? That's total surrender to the supremacist project."

Figs.17-20. Rythm Mastr (1999–present). inkjet prints

How then does Marshall escape the paradox? He simply embraces it. Marshall wants us to question the genre classifications which ascribe merit to art, even as his work fights in the same weight class as the Old Masters in the collection of the Royal Academy. He paints fluently within the traditions of Titian as he does with Manet, shifting seamlessly to adopt the traditional motifs of precolonial Kongo or Yoruba, knowing that his expression compels attention from the descendants of both traditions. Marshall does not petition for inclusion. He does not "demand to be seen" by the Western tradition, he does not claim the African tradition or subvert the European tradition as a one-dimensional act of resistance. Instead, he begins from his world, that of Black America—a product of the West, but born of Africa. Marshall demonstrates that the toolkit of Western visual culture, when refracted through Black experience, can be both conscious of whiteness yet rooted in Black interiority. His paintings lay claim to a more universal representation of human experience, achieved not merely by asserting the presence of Blackness in art history, but by painting Blackness as fact, then as figure, and only then as philosophy. And in doing so, he makes Blackness the indispensable force that carries art history forward.